In case you hadn’t noticed, we are now in the platform age.

The initial explosive impact of platforms has now embedded itself within the social and economic relations of our societies. From Asia to Latin America, from Africa to Europe, it is no longer possible to imagine a day passing without using some app to access a service, checking the web to catch up on the news, posting content on social networks or working in the cloud.

We live in an augmented reality that will soon be swallowed up by the Metaverse, while workers are constantly having their lives expropriated in the form of data. It is no longer a question of if and when, but how: the productive fabric of contemporary capitalism has found its infrastructure in the development of digital technologies and platforms. The point, then, is to politically manage this transformation.

The prophets of business as usual enthusiastically repeat the same mantra: let the market do its thing and the money will trickle down to everyone… sooner or later. Whereas policy makers try to take cover from the fantastic beasts that the Leviathan has allowed to grow up beside it, threatening its supremacy. Then there is the vast and fragmented family of those who would once have been called “leftists” – revolutionaries, reformists, red, black, green and any other colours you can think of. Perhaps today some of them would prefer to be called accelerationists because they believe that pushing technological transformations to their extremes would result in the economic and social overcoming of capitalist relations. Others instead suggest a “Socialism 4.0”, calling for the nationalization of the means of production, or rather, of the platforms. Of course we shouldn’t forget the neo-luddites, who want to wave goodbye to the metropolis and its digital machines to return to the enchanted and primitive world of the countryside. We hope we haven’t forgotten anyone… We should mention that spectre Marx talked about, which frequented the pubs but was wary of offering recipes for the future. Does it make sense to speak of communism today? Could there be a platform communism? You won’t find the answer in this manifesto, only a suggestion.

We will try to summarise that real movement in point form, attempting to describe that ongoing transformation that we call platform capitalism – its system of machines and living labour, its accumulation of data and of digital and material value – and see if we can understand how to use its contradictions as a lever for abolishing the present state of things.

We are immersed in contradictions: we talk about wages but are at work 24/7; there would be no social media if we weren’t continuously cooperating on digital platforms, but very few people benefit from the wealth that this produces; we can monitor any activity in any part of the world at any time, use software to spy on anyone we like or drop bombs with drones, but we are unable to guarantee health and education to most of the world’s population. It seems there is no alternative to platform capitalism: at most we can carve out our own niche for survival or delude ourselves that one day we will tame the Beast. If we think of the real as something compact and homogenous, then realism is a conservative political ontology. We prefer to think of the mole exploring underground, digging its tunnels in the earth until the building above collapses. You’d probably like us to tell you a little more about platform capitalism.

We will now summarise in 11 points what we see as the characteristics – and contradictions – of the new era.

| Genealogy | Digital platforms reflect the broad and general transformation of the structures of production which began at least half a century ago and can be divided into five steps. The first began in the 1960s, when the “logistics revolution” expanded production on a global scale and the circulation time of goods became part of production itself. The second took place in the 1980s, when consumption began to dictate and directly condition the rhythms of production: the so-called “retail revolution” in which Walmart was the paradigmatic actor. The third step happened at the turn of the millennium with the advent of the dot-com economy, in which the World Wide Web became the terrain not only of expanding social relations but also of new forms of enterprise. The fourth coincided with the 2007/2008 economic crash: dozens of platforms were set up (from Airbnb in 2007 to Uber in 2008) and the capitalist productive model moulded itself around their development. The fifth step arrived with the Covid-19 pandemic. The need for social distancing and smart-working combined to reshape the concepts of mobility, sociality and work, accelerating the substantial platformisation of society.

In short, the centrality of digital platforms now seems to be uncontestable. On the one hand, they are the forms of enterprise best adapted to the new relations of production in which everyone is at the same time a worker and a consumer within diffuse and fragmented spaces. On the other hand, the new structures of production give them a political and economic power that benefits them in the race to tomorrow’s world, a physical-digital hybrid incarnated in Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse project.

| Power | Power is today also embodied in digital platforms. Part of this power comes from the fact that the general platformisation of society, its self-definition on and through digital platforms, ends up favouring the increasing overlap between digital infrastructures, processes of accumulation and social cooperation. These platforms determine political choices, condition public opinion, and sometimes increase the emergence of anomalies such as the “Arab spring”, or, more recently, the protests in Chile or Hong Kong. They have a logistical power that allows them to extract and manage data flows, thus determining regimes of mobility and forms of inclusion and exclusion.

A tangle of non-state actors has grown up alongside the Leviathan. They interwine, overlap and collide, shaping new geographies of power. So the platforms are not themselves the new Leviathan, but they are a powerful part of the structure of the new technology stacks within which contemporary governance is embedded, and which also contain state sovereignty. The rules laid down by the algorithm sit alongside the laws fixed by codes.

| Infrastructure | Marx wrote that capital is a social relation between people mediated by things. We would add that, in today’s generalised regime of “things”, infrastructures take on a particularly important role: they are the skeleton that holds up the multiplicity of social interactions, it is along them that the flows of goods, capital and services run. In platform capitalism a decisive part is played by the digital infrastuctures that are owned and governed by Big Tech. Companies like Google, Amazon and Tencent (the operator of China’s WeChat) make up the social-but-not-public fixed capital of a society which sees the merging of the material and the virtual in one “reality”.

Since the economic crisis of 2007/2008, all kinds of platforms have ‘infrastructured’ the digital space, appropriating social cooperation and expropriating the libertarian imaginary that had seen in the web a land without masters. Like material infrastructures, the platforms establish a certain mobility regime, connecting but at the same time also restricting and compelling movement. It is difficult to travel in Europe today without booking an Airbnb, to have access to a “community” of users as large as that of WeChat in China, or to have as wide a choice of restaurants in Latin America as that offered by the app Rappi. These businesses own nothing – not a house, a restaurant, or any content – apart from a digital and material infrastructure that they make available to their users. Although the previous “alternative” channels are not going anywhere, the current hegemony of the new platforms/infrastructures has become clear. This dominant position means platforms inevitably gain political power of a governmental kind: they control, anticipate and determine our behaviour. While the state bases its notion of sovereignty on the occupation of a determinate territory, the platforms construct their power through governing the cloud. Thanks to their capacity to “extract” data, they have the power to bargain (if not to compete) with the state itself, a power that is perhaps greater than ever before seen in capitalism’s long history. At the same time, as infrastructure, they are a contested battleground within which new and unprecedented forms of struggle could arise.

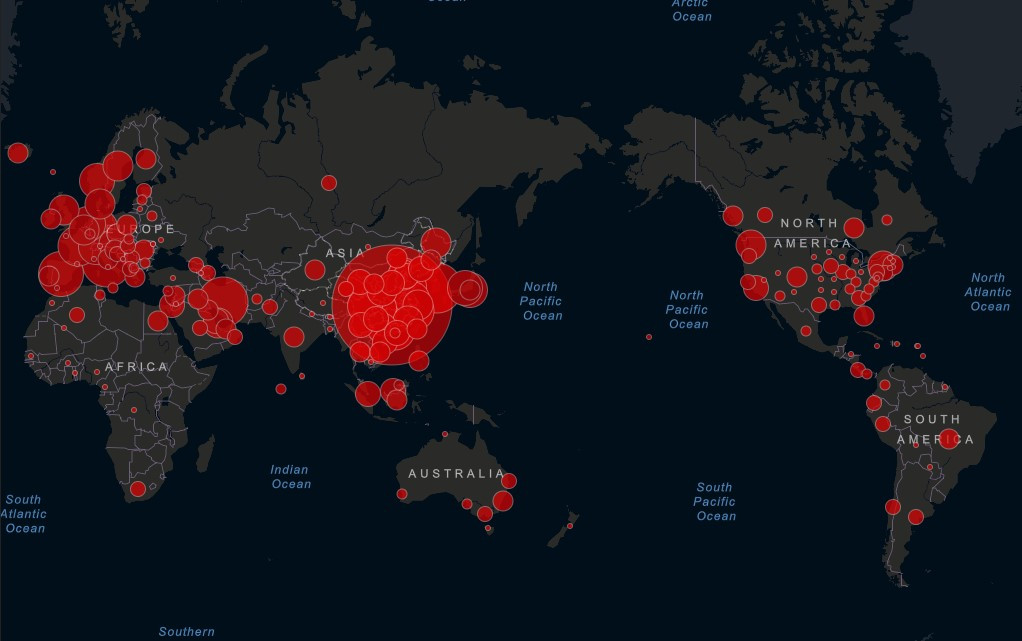

| SpaceTime | Platforms are not simply technological tools, but a constantly evolving result of social relations. They act on a planetary scale, feeding themselves on the heterogeneity of the different metropolitan contexts, continuously being shaped with and by them. They are ecosystems engaged in the consumption of human and environmental resources that determine multiple spatial-temporal regimes. They have a reductio ad unum ability based on who has ownership over algorithms, data and other means of production. Platforms represent the tendency of modern geographical scales to collapse. By their very nature, they cross national scales, reproducing themselves trans-locally, creating urban local hybrids, and opening up new spaces of accumulation aiming at new projects of colonisation – from the interplanetary space of the universe to the digital space of the Multiverse.

The telluric motion with which platformisation has crossed, decomposed and recomposed spatiality means it is no longer possible to understand social, political and economic phenomena by starting from predefined scales. Unlike other “technological” innovations in the history of capitalism (such as the scientific organization of labour) or the long and laborious construction of infrastructure such as railways and motorways, the “platform form” has developed circulation almost simultaneously across the globe. Platforms weave together plural historical times, recording the past to anticipate the future, and allow for the overcoming of the dichotomy between the virtual and the real. In other words, they generate space-times that not only continuously lead back to different types of infrastructure (transoceanic internet cables, data centres, click farms, cloud computers, etc.) and concrete assemblages of labour power (crowdworkers, prosumers, drivers, riders, programmers, etc.), but which should be fundamentally understood as existing in the interweaving of digitalization and material processes.

| Metropolis 4.0 | The process of platformisation is an urban process that, within a more general collapse of geographical scales, acts simultaneously on a global and local scale. This should be seen as involving two processes be read on two levels.

The first refers to the mutations caused by the digital platforms on the urban, which has multiple effects: firstly, urban agglomerations are the ideal terrain from which platforms can extract value – in them they find vast pools of available labour, data mines and considerable potential for innovation that can be subsumed; secondly, platforms have a profound infrastructural effect – just as in the last two centuries cities were broken up and redrawn by railways, motorways and airports, platforms now decompose and thoroughly redefine urban flows; thirdly, the platforms further globalize the urban, affecting its forms of property and command, as well as its imaginaries and the ways it is crossed; and fourthly, high tech urbanism develops its own architecture and specific regimes of habitation that increasingly resemble navigation practices.

The second concerns the platforms as a form of urbanization of the internet. Just as happened historically with the urbanization of the countryside and other non-urban spaces (“infrastructur-ation” plus political power), platforms already started urbanising the space-time of the internet after the first wave of the World Wide Web at the end of the 1990s. Their partitioning into apps managed by smartphones, their closed and proprietary nature, and their political power and infrastructural activity make them into the urban actors of the internet. The conjunction of these two processes means we can speak of a Planetary Metropolis 4.0 in the making.

| Geopolitics | There is too often a tendency to separate digital entities from territorial entities, platforms from the state, the space of flows from the space of places, the network from institutions. But the internet and the socio-economic actors that inhabit it are not neutral, and neither do they move in an ethereal space completely separate from the different physical geographical scales. On the contrary, today digital innovation’s primacy is geopolitical, within a more general process of the redefinition of globalization. If, on the one hand, platforms have an effect on state territoriality, imposing norms and forms of life through their power to manage flows, on the other hand, states are working on building alliances with digital companies or on creating autonomous infrastructures for the control and use of data. The digital colonialism of platforms – that penetrates urban spaces to subsume their productive and social forms – is counterbalanced by the digital sovereignty of states, who attempt to impose the power of the Leviathan on these new infrastructures. So, rather than exalting states as the enemies and regulators of digital platforms, we need to understand how laws and algorithms, the Leviathan and the platforms, build and stratify relations, sometimes working against each other and sometimes collaborating.

| Mythological machines | Platforms are not simply economic actors that affect political forms and social relations; they do not act exclusively on the material plane of production and extraction. They are also mythological machines that produce a symbolic and value imaginary which legitimises their actions and fortifies their operations, creating a narrative about the type of work, societal model and collective values we should strive for. It is no surprise that the platforms themselves are the product of a specific neoliberal imaginary, the so-called Californian ideology, combining hippy creativity with yuppy careerism. In this vision, internet and technological innovations are the perfect tools for enhancing humans’ entrepreneurial character, towards the creation of a freer and richer society thanks to the full automation of production and the support of artificial intelligence. This narrative not only legitimizes the power of the platforms through a particular set of values, but also has concrete material effects on the capacity to force living labour towards its own self-valorisation within the labour dynamics activated by the platforms. What’s more, it attracts the financial investment that digital companies need to survive within an economy of promises pledging boundless profits to those who manage to gain a monopoly of the market. Thus these mythological machines both conceal power relations and reinforce their grip on reality through their ability to activate a complex set of affections, emotions, values and aspirations.

| Finance | The intertwining of digital platforms and finance develops on a number of distinct but intersecting levels. On the one hand, finance supports the development of the platform model, which began in the global economic-financial crisis triggered in 2007-2008 and further accelerated with that generated by Covid-19. As is widely known, the platform model is based on the decline of the company-paradigm and on the speculative logic that allows actors like Uber, even in their early days, not to generate dividends but to have high value on the stock market motivated by an economy of promises of future profits.

However, there is another side to this intertwining of finance and platforms: the devalorisation of work on which the platform model is based, and its “capture” within digital infrastructures, are increasingly based on the production of indebted labour. Again the case of Uber is emblematic: while workers are attracted to the platform with the promise of increased autonomy, many need to go into debt in order to buy the means of production to be able to work. Thus the mirage of “free” and independent work is substituted with the reality of workers immobilized by debt and by economic dependence on the platform. La boucle est bouclée. There is also the way that digital platforms, algorithms and blockchains are changing finance: from micro-trading to NFTs and cryptocurrencies, finance itself is now becoming platformised. There is a new push towards the financialisation of society, with the promise that anyone can become an investor and anything can be a token to be traded.

| Work | Digital platforms make it possible to incorporate social cooperation processes within the logic of valorisation and finance. This mechanism isn’t new, but the platform model allows it to develop at unprecedented levels of intensity and on wider geographical scales. Within it, the erosion of the traditional relationship of wage labour does not imply a reduction in work, but its extension to and redefinition in new places and tasks, making the distinction between work and life increasingly blurred. In particular, the acceleration of the commodification of social reproduction (understood here in the broad sense of activity allowing for the reproduction of the life of individuals) that the financial crisis generates – and the resultant erosion of social spending and decline of its socialization through national welfare systems – finds a new impetus and outlet in the platform model. Mobility, food, care and domestic work are just some of the new frontiers in the platform model’s expansion.

| Algorithmic subjectivities | If capitalism is a social relationship mediated by things, then platform capitalism produces algorithmic subjectivities through digital devices, transmission protocols and standards, and applications and software. Platforms are governmental actors moulding our conduct and stimulating collective behaviours and passions. Cyborgs are no longer the political horizon of a world to come, but are already here, produced by the power of the algorithm and the pervasiveness of digital technology. We are cyborgs when we aren’t able to find our way without Google Maps, or when we speak to a voice assistant in order to locate a package.

Algorithmic subjectivities are constructed in the augmented metropolis, from when we are crossing the infosphere to when we are working in the cloud, from artificial intelligence to bioengineered implants. There is a blurring, if not the complete disappearance, of the borders between human and machine: today we live machinic lives, standardized and manipulated by new computers, big data and apps. Machines “come alive”: through machine learning, artificial intelligence and VR visors they replicate creative activities and construct parallel realities, mastering some of the functions of living labour, especially in the management field. Yet we are not condemned to live like automatons or to pursue the neo-liberal dream of being your own boss on this or that platform.

We don’t believe that we must analyse the digital simply in terms of domination. There is a proliferation of autonomous subjectivatisation in the web of the network: flaneurs who roam the city trying to enjoy the services provided by new technologies without being caught in the hunger for profit; digital nomads who move from one platform to another, following their own personal strategies; tang pingers who refuse to work at all; and the “social workers” framed by the Italian operaismo that reveal the power hierarchies behind the algorithms.

| Battlefield | Digital technologies and platforms cannot be framed simply within a dynamic of domination; sabotage is not the only resistance possible. Their development creates a battlefield between subjects and antagonistic forces whose result is not given and whose stakes are capitalism in its totality. If digital platforms aspire to a world without bottlenecks or conflicts but only flows connecting commodities and people, living labour constantly throws a spanner in the works in order to defend itself from constant labour, initiating resistances that contain a different vision of the use and organization of digital machines and which challenge the power of the algorithm and the concentration of wealth in the hands of those who own the codes.

Platform capitalism’s strength lies in its extreme resilience, which comes not simply from its capacity to shape its operations according to the specific context in which it is rooted, but from its ability to constantly incorporate that which is generated outside and against its action, transforming anomalies into variables integrated into the evolution of the algorithm. This oscillation between inclusion and subtraction, standardization and turbulence, demonstrates not only the power of the platforms but also the irreducible power of living labour. The latter is the real driving force of platform capitalism, without which its standards and predictions would not be able to get a grip on reality. And so, given this, how can we subtract ourselves from the resilience of the algorithm and, at the same time, take control of it?

And so we return to our initial and most important question. How can we act politically in the face of these transformations? Or better, what alternatives do the contradictions of these transformations give us? Is it enough to take control of current power relations or do these power structures themselves need to be radically rethought? We won’t try to write our own recipes. Yet you probably hoped to find not only a description of the present state of things but also a starting point from which to change them.

We would thus like to have a go at engaging in a bit of political imagination, beginning from the real in order to get to the possible. Let’s take a company that is a symbol of platform capitalism, a Big Tech company like Amazon, let’s think about its logistical capacity to coordinate and manage flows across the globe, its computing power that allows it to locate any package instantly, and the number of products and services that it offers and innovates. Now let’s think for a moment about what we could do if these IT, logistics and production capacities were organized collectively, not for the profit of the few but to allow everyone to work less. A slogan comes to mind, we’re not quite sure where we heard it, but we liked the sound of it: soviet power plus electrification. We could change it to: peer-to-peer plus digitalization.

Perhaps we can activate the contradictions of our present towards a platform communism that begins from these two principles. If the digital infrastructures of platforms are centrally managed, we can also imagine overturning their potential in a management that is extensive but localized, under coordinated and general control. Blockchains show there are many different types of network. The point is to remove them from processes of centralization and monopolization by taking them over and sharing their ownership with everyone until we abolish the regime of private property. Some platforms have become so infrastructural that they are now essential to our societies. However, it is not enough to take control of them, we also need to change the organizational principles that determine the hierarchical and asymmetrical power within them. How? By democratizing them. Peer-to-peer!

We have been made to believe that we live in a sharing economy, and so let’s take them at their word, let’s demand collective property until property is abolished. This implies a third programmatic point: we need a universal guaranteed income rather than a wage. We have seen that data is today the most coveted commodity. We are constantly producing data wherever we go, and platforms are continuously using it to adjust their calculations and their management and control processes. The centrality of the wage and its measurement by labour time are long gone. We have no nostalgia for Fordism, we prefer automation that relieves physical effort and expands creative possibilities. The most important thing is to remove ourselves from the blackmail of employment. Besides, looking at the assets accumulated by some venture capitalists, we don’t seem to be living in an age of scarcity.

Towards a world of plenty for all!